Israel

Changing Attitudes towards Zionism among American Jews—An Interview with Zachary Lockman

Zachary Lockman speaks to Lori Allen about the history of Jewish support for Israel in the United States. They discuss Lockman’s views on the changing attitudes towards Zionism among American Jews over the course of the twentieth century and the new spaces for criticism that have emerged over the pa

Indigenous Wine and Settler Colonialism in Israel and Palestine

In 2008 the first Palestinian wine made from indigenous grapes was released, introducing a discourse of primordial place-based authenticity into the local wine field. Six years later, Israeli wineries started marketing a line of indigenous wines. Since then, a growing number of Palestinian and Israe

Settler Entanglements from Citrus Production to Historical Memory

Although settler colonies are often depicted as unique and distinctive, Muriam Haleh Davis argues that analyzing settler colonialism in a global framework reveals their multiple commonalities. Here she examines the large-scale production of citrus in Algeria, Israel and California as one fascinating

Settler Colonialism in the Middle East and North Africa: A Protracted History

Settler colonial studies developed as a distinct field of research to address the particular circumstances of settler societies. Since its advent in the 1990s, this field has only marginally considered the Middle East and North Africa, focusing instead on the Anglophone settler societies of North Am

Settler Entanglements from Citrus Production to Historical Memory

Although settler colonies are often depicted as unique and distinctive, Muriam Haleh Davis argues that analyzing settler colonialism in a global framework reveals their multiple commonalities. Here she examines the large-scale production of citrus in Algeria, Israel and California as one fascinating

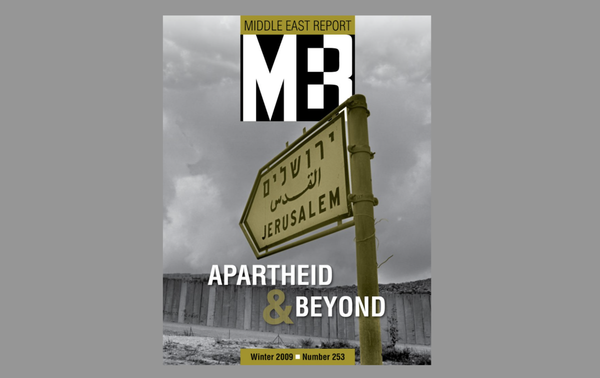

Revisiting MERIP Coverage of Israel as an Apartheid State

The recent upsurge in analysis of Israel as an apartheid state has peaked again with Amnesty International’s February 2022 report. The willingness of mainstream non-governmental organizations to use the language of apartheid marks a shift in the terms of the debate—one that builds on a long history

Tracing the Historical Relevance of Race in Palestine and Israel

The global conversation about race and racial oppression in recent years, which has reached new levels of visibility since the summer of 2020, has emerged largely as a reaction to police violence in the United States and the work of the Movement for Black Lives coalition. Its global reverberations h

Selling Normalization in the Gulf

When the UAE and Bahrain normalized their relations with Israel, the countries' leaders justified their actions as beneficial to the Palestinian struggle for statehood. Elham Fakhro explains how this rationale quickly fell apart and shifted, revealing deeper economic and strategic goals. Fakhro also

Three Decades After his Death, Kahane’s Message of Hate is More Popular Than Ever

Although Meir Kahane was assassinated 30 years ago, the violent and hateful legacy of his ideology continues to shape Israeli politics. David Sheen's in-depth and long-term investigative reporting sheds light on how the intricate web of Kahanist influence is pulling Israel further and further to the

The Dilemmas of Practicing Humanitarian Medicine in Gaza

Humanitarian medical aid was developed to provide life-saving assistance to populations suffering from war and disease. What happens when this model is applied to help those living under occupation and coping with chronic deprivations and long-term siege conditions? Osama Tanous, a Palestinian pedia