Rebuilding Gaza from the Ground Up

An Interview with Minerva Fadel of Architects for Gaza

An Interview with Minerva Fadel of Architects for Gaza

For MERIP’s winter issue, Reconstruction and Ruin, issue editor Hannah Sender spoke with Minerva Fadel, a doctoral researcher at the University of Westminster and a founding volunteer with Architects for Gaza (AFG). Established in November 2023, AFG brings together architects, academics and students working in dialogue with Gaza’s municipalities and Palestinian universities to explore community-led approaches to reconstruction, education and material repair amid ongoing devastation. This interview was conducted in November 2025 and has been edited for length and clarity.

Hannah Sender: Tell us a little about yourself and how you got started with Architects for Gaza.

Minerva Fadel: I’m currently a doctoral researcher at the University of Westminster. I work on architecture in relation to conflict and peace, post-conflict terrains and how we deal with fractured landscapes. Before starting my PhD, I founded Re-think Housing Studio, which is an online studio I set up with other researchers and architects from Syria, where we’ve been debating sociopolitical, interdisciplinary and participatory aspects of architecture—particularly housing and everyday architecture—and how these relate to society, conflict and heritage.

I started volunteering with AFG from the very beginning, in November 2023. I first heard about AFG through Yara Sharif, my PhD supervisor, who, together with Nasser Golzari, set it up. I understood it as an attempt to bring people together and see how we could do something for Gaza. At the very beginning, AFG’s work was mainly reflecting on what could be done [in response to the genocide]. Those early discussions, as I remember them, were about exploring what might be possible. We were driven by our desire to do something for Gaza, even if we didn’t yet know exactly what that would be. Over time, those meetings naturally started to shape what AFG could be, what kind of structure it needed and where its focus should be. From there, things gradually settled around two main areas: rebuilding and education, which then became the main clusters we worked through. In the Education cluster, I worked with other volunteers to deliver online sessions for Gazan students, an initiative with An-Najah National University in Nablus. Then I became more involved in the Rebuild cluster, an initiative in partnership with the municipality of Gaza. Within the Rebuild cluster we were working with an understanding of reconstruction and repair that was community-led and rooted in the Gazan context—starting from people’s lived experience and seeing Gazans themselves as central to shaping what the process of rebuilding and repair could and should be.

The first project under the Rebuild cluster was testing and exploring recycled materials and ways of self-help. This is inspired by Gaza’s initiatives to recycle available materials for reconstruction. The outcome was fragments of a mobile clinic that could be used by doctors. The initial design concept was based on earlier work by Yara Sharif and Nasser Golzari on self-help typologies for Gaza that were developed with UN-Habitat and Gazan local partners. The testing and making process brought together students from the University of Westminster alongside design tutors, technicians and other volunteers from AFG who joined at different stages of developing and installing the unit. The work also involved external partners, such as the Mobile International Surgical Teams, who shared insights from the ground about the kinds of spaces and functions they might need—particularly around the idea of the unit operating as a mobile clinic.

The pavilion—Gaza Off-the-Grid Experimental Lab: A Work in Progress—was built at the University of Westminster as part of the London Festival of Architecture in June 2024. A developed version of it was later exhibited as part of Objects for Repair at the 19th Venice Architecture Biennale in May 2025.

At the opening of the London Festival of Architecture exhibition, as I recall, the curators were very clear that the pavilion should not be read as a solution or a fixed proposal. Instead, it was presented as an attempt to think through where to begin—to set up a possible scenario working with available materials or a platform for testing ideas and inviting relevant communities to be part of that testing. It was also meant to open up a broader discussion about whether, and to what extent, it is possible to work with communities on the ground and with materials that come from the site itself. If you look at the pavilion, it uses materials that people can realistically find and access locally, such as wires that can be bent and adapted for different purposes. These materials were deliberately chosen as a starting point because they are close to what people have already been using to survive their everyday life and to build a shelter.

Hannah: It sounds like a commentary on what has happened to Gaza. By virtue of saying that these are the materials that people have, you're also saying, “look at the devastation. We're working with rubble and wire.”

Minerva: Yes, exactly. The pavilion has four partial walls, and each one works with a different material, things like brick made of crushed concrete and clay, fabric, corrugated metal and reinforcing bars. There was also folding cardboard used for drawers and a bed that could be folded away.

These kinds of contradictions bring you closer to the reality in Gaza, which, for me, felt like a mix of deep suffering and creativity at the same time—a place and people that you learn from and that remind you, even as a professional, to stay humble.

The design was informed by a series of online research sessions involving a large number of architects. Together with Loay Dieck, an AFG member, I was mapping the situation in Gaza at that time, mainly through online materials, documentation and articles, and we were focusing on two main points. The first was self-help and everyday practices: how people were finding their own solutions to daily needs. There were images that really stayed with me, like desks stacked on top of each other to act as shelves, a child responding to the fear of darkness by creating a simple electrical circuit to light a small bulb or children using a hanging wire to play with. These kinds of contradictions bring you closer to the reality in Gaza, which, for me, felt like a mix of deep suffering and creativity at the same time—a place and people that you learn from and that remind you, even as a professional, to stay humble.

The second focus was what you might call an atlas of materials, looking at what materials were actually available on site or being developed and adapted by Gazans themselves, such as recycled blocks and the Green Cake brick (a sustainable building block developed in 2016 by Gazan engineer Majd Mashharawi made from war rubble and ash to provide a lightweight, low-cost, locally sourced material for rebuilding homes in Gaza). In relation to (re)building, we also mapped how people were fixing tents to the ground, for example, often using sandbags. That idea of grounding then found its way into the design through the use of cages filled with rubble. In essence, the work was really an attempt to bring different ideas together in a creative way but not in any final or resolved sense. It was more about setting up a platform for testing ideas.

And yes, whether intentionally or not, it does also read as a statement about the scale of destruction in Gaza, where rubble has effectively become one of the main building materials. It resembled the memory and history of the place and was explored as a tool to mark home, street and neighborhood.

At the moment, within the Rebuild cluster, AFG is working with the municipality of Gaza on specific sites that have been destroyed and is developing proposals that explore how those places might be rebuilt through a community-led approach.

Hannah: How did you select those sites? Were they selected by the municipality of Gaza City? And how did that collaboration come about?

Minerva: The municipality was part of the conversation from quite early on. AFG was approached by the municipality. A key workshop in October 2024 that brought AFG and the municipality together marked a shift towards starting to work with actual sites. During the workshop, professionals from the municipality shared their own briefs and visions for reconstruction. They were thinking ahead to a moment when repair and reconstruction might become possible, and they identified certain sites that they felt would be important starting points. They nominated around five or six sites. Their work stems from the belief that the process of healing Gaza should not wait. It should start immediately.

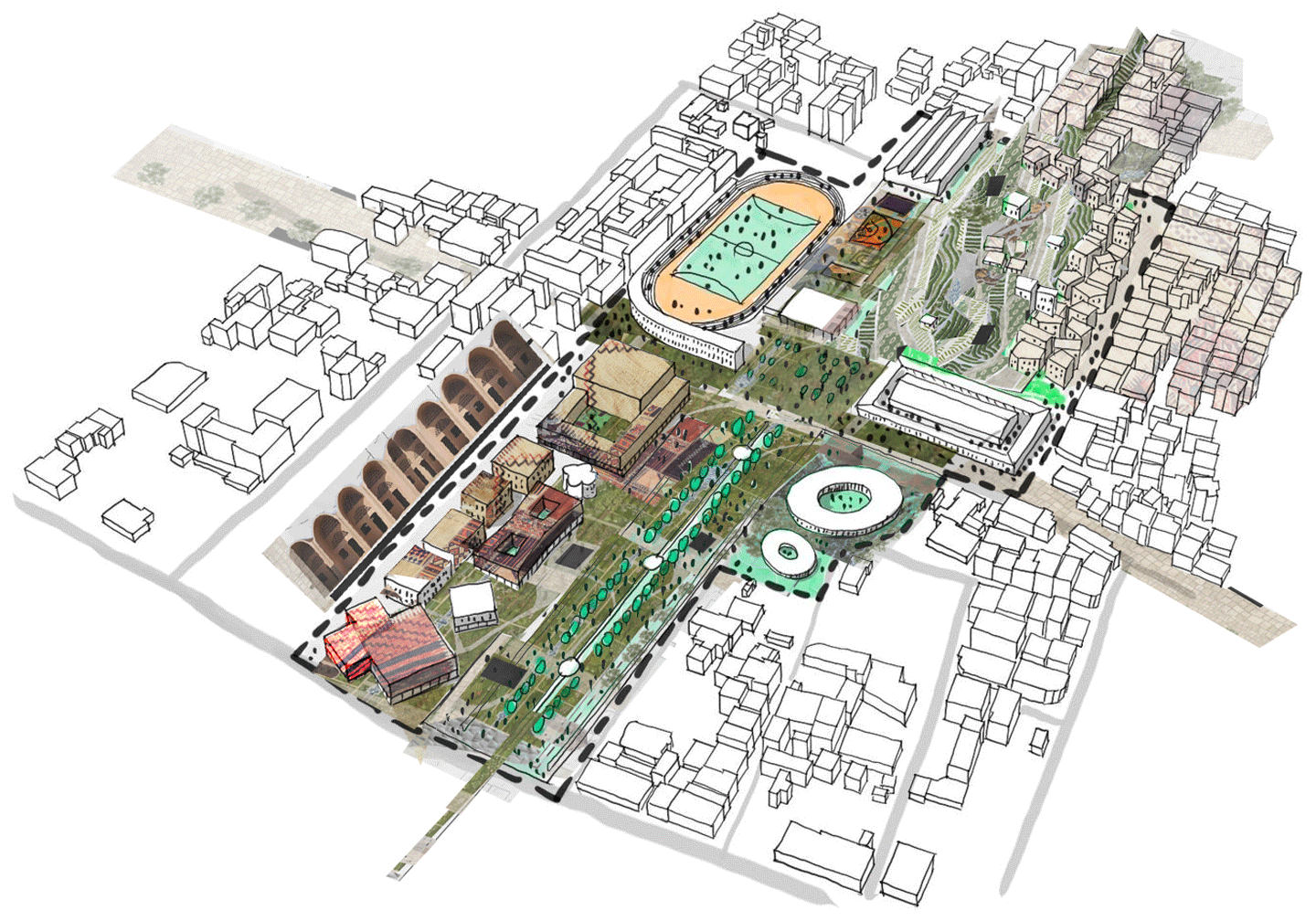

From there, AFG began focusing on two of those sites based on their importance and urgency to the city’s recovery. One of them is the Yarmouk Cultural Complex at the heart of Gaza City. It functions as both a cultural and commercial hub. It’s also a very large and complex site, which brings its own challenges. It includes a stadium, a historical mosque, many shops and areas of green space. Since then, there has been ongoing discussion between the AFG team, the mayor and the wider municipal teams. Over the course of about a year, with a high level of commitment from the relevant AFG teams, the proposals have been gradually developed and refined together with the municipality. It’s very much still a work in progress with a number of stakeholders consultations. The work involves an overall concept strategy for the site that is aimed, at a later stage, to be further designed by local Gazan architects.

The second site is the lagoon, Sheikh Radwan Reservoir. It has been used as a point for providing water to the area. Because of the scale of destruction, however, the lagoon has become polluted, and there are significant infrastructural issues associated with it. The project looks at both immediate and longer-term strategies for the site, including approaches to water management, public provision and a building that responds to specific requests from the municipality.

Hannah: Do you have a sense of what Gazans are doing now around those sites? Are they rebuilding? Are they coming back?

Minerva: Both Rebuild teams have been involved in mapping activities to better understand the context on the ground. And, yes, there are small-scale, emergency attempts to build, consolidate or stitch together destroyed homes and tents at different scales. However, access to materials remains extremely limited, if available at all.

When the AFG team working on the cultural hub carried out the initial mapping in late 2024, the stadium area was full of tents and was functioning almost as an emergency shelter. Part of the challenge has been mapping things that used to be there but are no longer present. This includes key historic monuments and buildings of significant value. These were mapped by local architects in Gaza and carefully identified in order to mark and honor their significance.

Hannah: How are you all thinking about heritage? If it's already been destroyed, how are you going back in time and thinking about what was there?

There was an ongoing attempt to revive some of the rituals and cultural practices that had been part of those sites as a way of engaging with heritage in a more intangible sense.

Minerva: The volunteers often had to double-check what they were mapping on the ground against older photographs, for example from newspapers or archived sources. A lot of effort went into piecing together information from different places and moments to identify critical buildings and rituals of importance. There was an ongoing attempt to revive some of the rituals and cultural practices that had been part of those sites as a way of engaging with heritage in a more intangible sense. As I recall, the Yarmouk Cultural Complex team had thoughtful and very careful discussions around what might work and what might not, particularly in relation to the community and to what is understood as heritage.

In the case of Gaza and the Yarmouk Cultural Complex, we mapped culturally significant buildings, sites and daily practices, both tangible and intangible. With the involvement of local architects and members from Gaza and the municipal team, a list of key buildings was identified to be protected and revitalized, as well as an inventory of key plants, trees and species that identify the area.

Hannah: Do you see that as a political maneuver? I see it as a form of hope, a way of saying that we know that this will end, and we have a vision for what Gaza will look like and who it will be for when this is over. Is that fair to say?

Minerva: Hope does seem to be present. I was actually noticing this recently while going through AFG’s Instagram page, where much of the work is documented, the word hope comes up quite often. The work AFG is doing asserts Gazans’ right to rebuild and reconstruct and their right to home. It also seeks to honor Gazans by placing them at the center of the process and challenging colonial forms of erasure.

I’ve also felt it more directly during moments of communication, presentations or events where people from Gaza were able to join us from there. Often, they were connecting from very dark spaces—dark in a literal sense because of the lack of electricity but also dark in relation to the suffering, the violence and the conditions they were living under. In those moments, Gazans were clearly struggling, but there was also a sense that somewhere, someone, like AFG, was trying to act, or push back, on their behalf. So yes, hope is definitely part of what AFG ended up presenting.

And I do think that centering community participation in informing design and planning is, in itself, a basic ethical practice as architects in the profession. It raises fundamental questions: Who gets to rebuild? Who has the right to be involved in the rebuilding process and whose visions and voices are prioritized?

Hannah: I assume that you as a team have had conversations about President Donald Trump’s development plan for Gaza. How are you positioning yourself as AFG in relation to these seemingly fantastical, far-fetched plans?

...imagining Gaza as an empty site for investment or fantasy while completely ignoring the people who live there, their suffering and their right to shape their own future.

Minerva: I think what we are doing, in a way, is confronting that narrative—the narrative where someone else decides, takes ownership over people and determines on their behalf what their future should look like. And this kind of narrative didn’t only appear with the Trump plan. I remember, even in the very first panel discussion we held in March 2024, a couple of months after AFG was initiated (Gaza Reborn: A Foot on Earth, a Hand in the Sky), part of my presentation referred to something I had seen on the news: an advertisement promoting real estate offers for plots on the beach in Gaza, marketed as places where you could build a holiday villa. That was a very clear and disturbing example of the same logic, imagining Gaza as an empty site for investment or fantasy while completely ignoring the people who live there, their suffering and their right to shape their own future.

Hannah: Recently Israeli settler groups were selling land in South Lebanon for Israelis to buy. They produced these strange renderings of what the houses would look like and they had renamed all the villages. Compared to what AFG are doing, here are two very different ways of planning and envisioning the city.

Minerva: Within AFG, these kinds of conversations often bring us back to a shared understanding that what we are doing is not just about a community-driven approach. It is about recognizing that communities themselves are the owners of the land and that AFG is working for them. AFG strongly underlines that the people of Gaza have the right to their land and their places, no one else. We also focus on who engages with the process of repair and rebuilding and for whose benefit, as well as how closely the local community is involved in shaping these processes. Ultimately the intention is to respond to local needs, instead of imposing a vision from outside. Of course, Gaza carries thousands of years of history—around 5,000 years—so land is deeply valued and passed down through generations. It is an integral part of people’s identity and belonging, not something that can be reimagined, divided, reallocated or be subject to a vision imposed from outside. Gaza is for Gazans.

Hannah: We've spoken about two AFG reconstruction projects, but tell us more about the work of the educational strand.

Minerva: The educational cluster involved teaching and some workshops with An-Najah National University as mentioned earlier. It focuses on empowering Gazan universities and students and assisting them in completing their education. The universities are back in action despite the destruction, and we continue to provide the support via our volunteers where needed. There has also been some written output coming out of this work. AFG has contributed to a publication focused on education, and there have been a couple of recent articles and publications linked to the education cluster and Gaza Global University.[1]

Hannah: Things have changed a lot since you first started. What are your priorities now as a group?

Minerva: At the moment, a significant amount of energy is going into the two projects in collaboration with the municipality of Gaza, which in themselves require a high level of commitment. This work goes alongside ongoing advocacy efforts. At the same time, AFG has just launched a seed fund to support and empower local Gazan architects, allowing them to further develop designs for specific sites in collaboration with the municipality.

Hannah: If people want to get involved, what would you recommend?

Minerva: At this stage, the best way is to contribute towards the seed funding and to join AFG as members, helping to amplify the voice of Gaza.

Support MERIP in providing critical, grounded reporting and analysis without paywalls. Make a one-time or monthly donation today!

[1] Mirna Pedalo, “The Tools at our Disposal: Architectural Pedagogy in the Face of Calamity,” Acta Architectonica et Urbanistica 1/1 (2025), pp. 168–177.