Burri Under Siege—How War Remade Everyday Life in a Sudanese Neighborhood

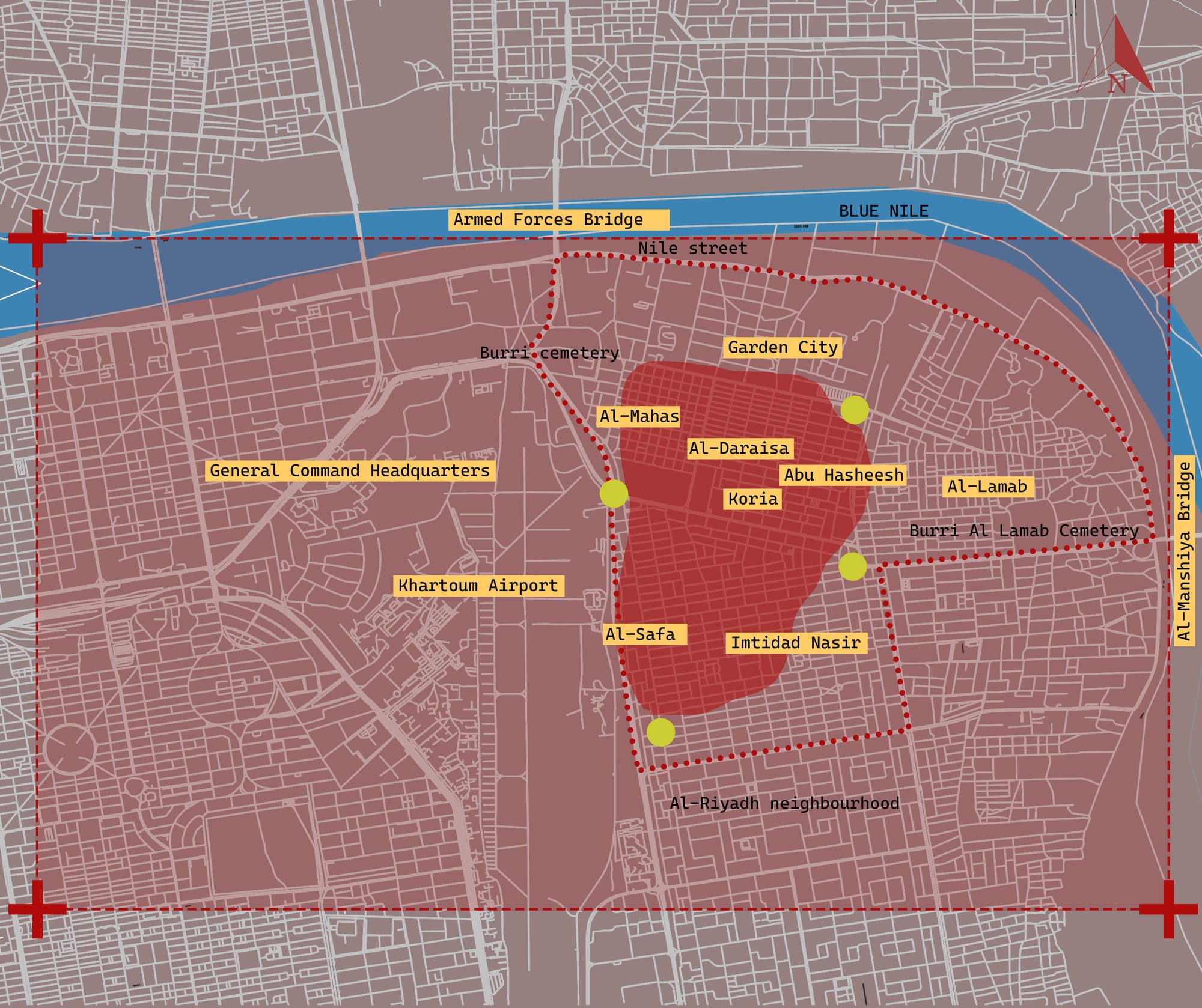

In March 2025, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) retook key areas of eastern, central and southern Khartoum. Their advance ended the Rapid Support Force’s (RSF) two-year siege of Burri—a neighborhood of eight residential areas in central Khartoum along the Blue Nile River.

As part of the metropolitan core that links the three cities of Sudan’s capital—Khartoum, Bahri (Khartoum North) and Omdurman—Burri lies in the shadow of numerous strategic and military sites: the Sudanese Military General Command headquarters, Khartoum International Airport, the presidential palace complex and a concentration of government buildings. It is also linked to Bahri and Sharq Al-Neel (Eastern Khartoum) through two critical transportation arteries, the Armed Forces Bridge and Al-Manshiya Bridge.

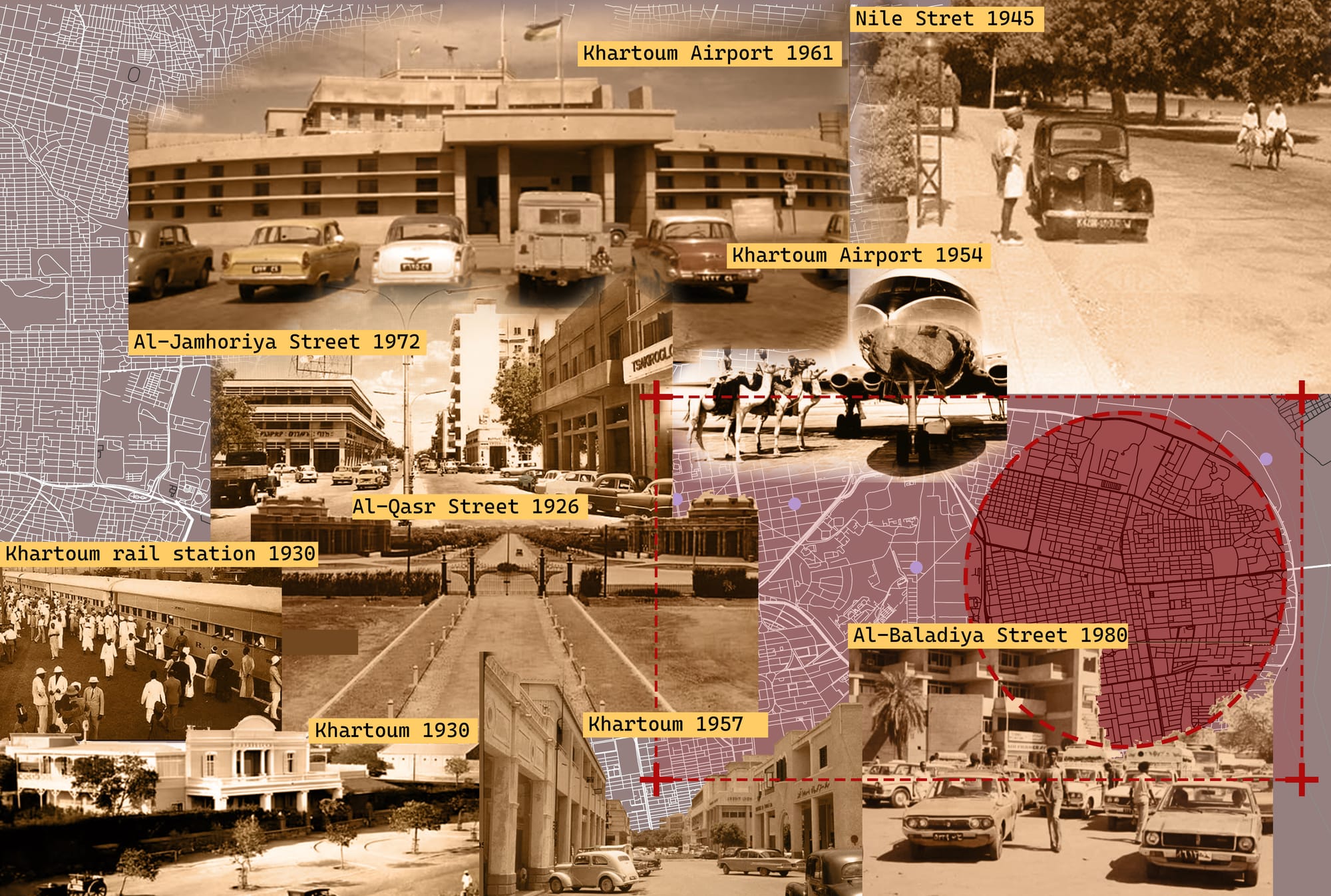

Military forces have long maintained a presence in the heart of the capital from the colonial Anglo-Egyptian period through independence to the present day, allowing successive regimes to impose control and keep a tight grip on the city. These spaces of military and political authority have repeatedly been contested by civilian protesters throughout Sudan’s history, such as during the uprising in 2018–2019 that led to the ouster of President Omar al-Bashir.

But in the current war that began on April 15, 2023, this urban morphology has for the first time transformed the spaces of Khartoum’s central streets and neighborhoods into a landscape of armed conflict. The struggle between the RSF and the SAF for control of the country has turned Burri and other surrounding neighborhoods into frontlines. When the RSF seized control of Khartoum’s airport in the initial hours of the war, they moved immediately toward the General Command headquarters. Burri, lying directly along this strategic route, became the focus of relentless assault. I spoke with five residents from Burri about their experiences during the two-year siege to understand how those trapped within these militarized and securitized spaces endured the violence and navigated their day-to-day lives.[1]

Othman was among the residents who lived under the siege for several months before relocating to Egypt. I connected with him in 2025 through a mutual friend from Burri. He told me that his area, Al-Lamab, located by Al-Manshiya Bridge, was one of the first in Khartoum to be invaded by the RSF, who advanced through this part of the neighborhood around the tenth day of fighting in April 2023.

“They were stationed in all parts of Burri to attack the General Command, and the largest concentration was near us,” he said. The RSF had approached from the south through a wealthier part of the neighborhood, Imtidad Nasir, bringing tanks and heavy artillery that rolled into the inner streets. Many of their troops occupied affluent homes there and in the nearby Al-Riyadh district to the south. From these positions they fired toward the General Command headquarters, while SAF forces returned fire from the west.

Caught in the crossfire, many homes and public facilities were destroyed within the first week, setting the scene for urban catastrophe. “Many supermarkets and shops where people could find food were looted or shelled during the first days of fighting,” described Ibrahim, one of the young volunteers who remains in Burri and participated in community aid during the siege. “Burri’s electricity and water stations were also hit.”

This destruction and targeting was part of a calculated military strategy by both RSF and SAF forces to render each section of the neighborhood unlivable, for Burri’s residents and for the troops holding them, clearing the way for the opposing side to advance and take control.

By the end of the first month, the RSF had established military positions within and outside of many buildings. The streets were transformed into military zones filled with checkpoints, security stations and surveillance points. RSF fighters entered Burri in large numbers and, according to one interviewee, their personnel changed over time. Each new group brought its own motives and methods of dealing with residents. Some took the situation as an opportunity to collect money and valuables (knowing no one could argue with them as long as they carried guns). They stormed homes, seized cars, looted shops and forced some families, particularly those living in newer buildings, to leave so they could occupy their houses. Others, however, tried to interact with residents in an attempt to normalize their presence and gain a sense of acceptance, claiming they would be governing Khartoum.

The new rules imposed by the RSF not only limited mobility but also redrew Burri’s internal boundaries.

The movement of people and goods was restricted and controlled internally through an extensive network of RSF checkpoints. The new rules imposed by the RSF not only limited mobility but also redrew Burri’s internal boundaries. Residents who left their homes did so at the risk of harassment or assault, and those who had to be in the streets avoided carrying phones and cash, out of fear of being robbed. The area effectively shrank into a set of sealed corridors. To the east, movement stopped at Dream Specialized Hospital, while to the west a large RSF base was erected at the Bee Petroleum gas station. Al-Safa Street to the south was sealed off, and to the north the furthest point anyone could reach was the Spanish Embassy on Al-Ma’arad Street. Beyond that northern line, and along Nile Street, RSF fighters occupied several government buildings and compounds, including the presidential palace, the Khartoum National Club and the presidential villas.

Nile Street is one of Khartoum’s most vital arteries. It runs parallel to the Blue Nile and connects the urban core to the bridges that link the three cities of the capital: Khartoum, Bahri and Omdurman. Its significance dates back to the British colonial period, when the governor’s palace and elite residences were first established along the river bank. Under Omar al-Bashir’s rule, the army further expanded its presence through new commercial investments and construction projects, including the Khartoum National Club, one of the army’s largest investments in the city. Once the RSF took control of Nile Street during the first two days of fighting, they were able to block all access in and out. For those trapped in Burri, the closure of this route disrupted the entry of essentials and cut evacuation paths.

These chokepoints and zones of securitization did not merely emerge out of the siege. They were the outcome of more than a century of urban planning that has woven military power into the fabric of Khartoum.

The military’s presence in Khartoum traces back to the formation of the colonial city in 1899 under Anglo-Egyptian rule. Its layout followed an axial planning that was widely adopted in most colonial cities at the time as it supported the military objectives of maintaining social order and enabling riot control. In Khartoum, a quadrillage of roads intersecting at right angles was created to form a chessboard-like pattern, designed to facilitate army surveillance and troop movements across the city center. Key military and government institutions, as well as houses of the European elite, were placed along the Nile and the main streets, further projecting state control. [2] The planning and construction of these buildings—including the General Governor’s palace—were carried out by military engineers between 1906 and 1912.[3] Throughout this period, the colonial authority worked on transforming the city to suit the interests of the military and political elite.

After independence in 1956, successive regimes reinforced this spatial order of concentrating military zones in the heart of the city. When the National Islamic Front, an Islamist party backed by the military, seized power in 1989 and ushered in the rule of Omar al-Bashir, the new government deepened urban militarization and expanded state land holdings across the country by expropriating private properties. This system was applied to seize strategic community-owned land in central Khartoum and its surroundings for the benefit of the state and its allies. The people responded with legal appeals and demonstrations that have continued even after the regime’s fall.

Al-Bashir’s regime entrenched its power not only through land policies but also economically by establishing military investment networks. In 1993, the Military Industry Corporation (MIC) was founded to oversee equipment production at large-scale military facilities located in Khartoum, including the Yarmouk Industrial Complex, El Shajara Ammunition Plant and El Shahid Ibrahim Shamseldin Complex for Heavy Industries.

Khartoum’s militarization intensified further with the emergence of the RSF as a rival political and military actor. Although the RSF had maintained a close relationship with the military leadership since 2013, its operations were largely concentrated outside the city, in southern and western regions. In 2017, the RSF gained legal legitimacy as an independent security force. Following this, the RSF began to expand its economic influence in Khartoum through investments and commercial activities.

During the transitional period after the fall of the al-Bashir regime in 2019, the RSF, supported by the SAF, expanded its operational footprint in the capital. It was deployed across Khartoum to guard military installations and secure strategic sites, including bridges, the national television station, the airport, the General Command headquarters and elite residential neighborhoods.

By the time war erupted in 2023, Khartoum was a city whose central arteries, public squares and riverfront land had been repeatedly reorganized around the protection and enrichment of military institutions.

By the time war erupted in 2023, Khartoum was a city whose central arteries, public squares and riverfront land had been repeatedly reorganized around the protection and enrichment of military institutions. Burri’s proximity to General Command, the airport and Nile-facing power corridors—where both factions of the military were stationed—played a decisive role in bringing the war into the neighborhood and in shaping how the siege unfolded.

The exchange of intense shelling and bombing between the two sides that erupted periodically throughout the siege destroyed much of Burri’s civilian infrastructure. Schools, health centers, pharmacies and stores were damaged or closed. The RSF also shut down several public buildings in the area, converting them into barracks and detention sites.

I met Amal, a friend’s relative, in her apartment in Egypt. She had left Burri after spending nearly two years confined to her home with her younger brother. Amal spoke about the daily struggle of living without electricity or water, with very limited access to food and medicine. A diabetic, she relied on a monthly medical prescription that became almost impossible to get. “I was able to get my medicine from the nearby pharmacy only once before the RSF looted and destroyed it,” she said. After that, it became too dangerous to sell or store medicine openly. A few volunteers collected what was left of medical supplies and hid them inside houses. They went door to door, delivering medicine to those in need without attracting the RSF’s attention.

Amal also recalled how risky it was to reach the only hospital that was still operating in the area. Often, it required makeshift transport, like the use of wheelbarrows, as the RSF prohibited driving cars or motorcycles within the area. Those accompanying the sick often had to engage in delicate negotiations with armed fighters at checkpoints or in random inspections. “The sick were treated at home or taken to Dream Hospital,” she said. The hospital had been taken over by the RSF, who forced the medical staff to work without pay under the threat of arms. “They admitted patients as they pleased, and if they suspected someone was from the army, they executed him,” she told me.

With hospitals weaponized, community volunteers mobilized supplies, enlisted volunteer doctors and established three improvised medical centers inside residential buildings across Burri, in Abu Hasheesh, Al-Lamab and Imtidad Nasir. These makeshift clinics provided first aid to those injured in the fighting. Many times, volunteers had to treat patients under bombardment and in complete darkness, without electricity or adequate medical equipment.

In addition to accessing medical care, the struggle to secure food began within a week of the siege. Shops along the main streets were frequent targets for the RSF, who looted them or took them over for their own use. Some families shared their meals with neighbors, but many low-income families went without food for days.

Mazin, an active community volunteer, stayed in Burri for more than a year before travelling abroad to care for his sick mother. During an online conversation, he described how difficult it became for people in Burri to access food, even when it was available. Some residents found a way to open small mobile stalls selling sugar, tea and bread, but prices were high and stock was limited. Mazin and his neighbors mobilized resources to establish takaya (communal kitchens). Takaya are deeply rooted in Sudan’s culture of collective care. Historically, these kitchens date back to the Ottoman era, often associated with places of worship that provided free food and shelter to travelers, the needy and anyone seeking sustenance.

During the siege, communal kitchens were funded through donations from the Sudanese diaspora and local non-governmental organizations. “We were the first volunteer group in Khartoum to start takaya, and later it spread across the capital,” Mazin told me. It was initially intended to support those who could not afford to buy food but later expanded to serve everyone as food became increasingly scarce during the two-year siege. The volunteers managed to open three central kitchens, one in a mosque and two inside residential buildings.

Mazin also recalled the dangers of bringing food into the area. The nearest open markets were in Sharq Al-Neel in Bahri. To reach them required crossing the Blue Nile via the Al-Manshiya Bridge. Traders were only allowed to pass after paying taxes to both RSF units stationed in Burri and SAF members on the opposite side. The situation grew even more difficult when both of the warring parties began taking over supply routes to local markets across the country, smuggling goods and food from neighboring countries into the areas they controlled for their own profit. In Burri, the RSF also appropriated humanitarian aid, disrupting the flow of food and medical supplies. “The RSF took control of the markets, seized supplies and even stole volunteers’ subsidy payments,” Mazin said, referring to the money given to takaya volunteers to buy supplies. “Sometimes they kidnapped traders and demanded ransoms.”

Mazin and others who worked to provide support are originally members of Burri’s neighborhood resistance committee (a grassroots network established during the revolution, before the war). With their deep knowledge of the area and strong social ties—many were from the same extended families—they took on negotiations with RSF commanders to secure limited movement outside Burri for the volunteers. They organized regular trips to Bahri under conditions set forth by the RSF. Multiple checkpoints were set up along the route where RSF soldiers boarded vans to inspect passengers’ ID cards, verify their residence and occupation and ensure none were affiliated with the SAF. Those who traveled outside had to learn how to negotiate with both RSF and SAF fighters—RSF on the Burri side, and SAF upon entering Bahri—to secure their safe return.

Former resistance committee members and others also stepped in to provide crucial educational support. Most of the neighborhood’s schools had been turned into military barracks, as Burri became a primary site in the capital for RSF arms storage and troop accumulation. Many students were trapped inside their homes, cut off from education and surrounded by a heavily militarized environment. Mazin told me, “We noticed a shift in the children’s mindset towards the reality of war—they were playing games repeating the names of weapons and artillery they hear around them.” The youth volunteers came together to create a makeshift learning center inside a residential building in Abu Hasheesh, a relatively safer area. Teachers from various parts of Burri volunteered to provide lessons based on the UNICEF distance learning curriculum. They converted the apartments into classrooms, playgrounds, storage areas and offices.

Not only the spaces of everyday life but also social relations—and even death—were profoundly restructured under the siege. The RSF sought to undermine people’s trust in the army and their hope for liberation, while simultaneously forming alliances among the residents. They recruited from within the neighborhood, sometimes tempting young men with promises of power, money or protection, and at other times coercing them at gunpoint. “We had to deal with them because they had the power of arms, and some people were threatened with execution if they did not cooperate,” Mazin explained.

RSF fighters in Burri used skin color as an indicator of ethnic and regional origin with lighter skin attributed to origins in northern states and perceived ties to political elites and SAF officers.

They used their military authority to dictate who could live and who would die. Amal told me that many killings and acts of intimidation were racialized or politically motivated, targeting individuals for their history of activism, family connections or even the color of their skin. RSF fighters in Burri used skin color as an indicator of ethnic and regional origin with lighter skin attributed to origins in northern states and perceived ties to political elites and SAF officers. They also controlled burial processes, reshaping the spaces of cemeteries. All burials required explicit RSF authorization, including approval of the burial site and timing. Amal remembered how, when someone died, RSF leaders would show up at the scene, deciding where and how a family could bury their loved one as a way to humiliate people and remind them who held power.

During the siege, burials that traditionally took place at Burri’s cemetery—at the crossroads of Ebed Khatim Street and Al-Ma’arad Street—or in Al Lamab Cemetery, were pushed into the interior of the neighborhood. Even when cemetery burials were permitted, they eventually became full, and families were left having to bury relatives inside their homes, front yards or along nearby streets.

Civilian adaptation to war and the redefinition of space for survival echoes patterns seen in other besieged cities. Omar Ferwati has chronicled how civilians and combatants alike reshaped architecture to sustain the resistance during the Battle of Aleppo (2012–2017) in Syria.[4] Those trapped in the city, much like the people of Burri, learned how to navigate their transformed surroundings and create new spaces for services and care—implicit acts of resilience against the violence around them. Similar forms of spatial improvisation were documented during the siege of Sarajevo in the 1990s, where residents repurposed both interior and exterior spaces to survive amid constant destruction and military aggression.[5] Yet, in Burri, survival was not only about reimagining space, it also meant learning how to negotiate coexistence with the enemy.

The war in Sudan still rages in some parts of the country, but Burri’s siege has been over for nine months as of this writing. By late March 2025, the RSF had launched a final campaign of looting and intimidation against those still trapped in Burri, a last attempt to seize whatever valuables remained before the SAF forced them to withdraw from the center. The news of the army’s recapture of central Khartoum was celebrated by military leaders as one of their greatest victories of the war. They touted breaking the RSF’s hold over the General Command headquarters, airport and the presidential palace as the restoration of national pride and political control over Sudan.

Yet for many residents, these celebrations ring hollow. The city lies in ruins, and it is hard to imagine a promising future at this moment. Meanwhile, the army—now acting as the officially recognized government—has already begun planning and implementing a series of what it calls rehabilitation and reconstruction projects under the motto of restoring life in Khartoum within a few months. This approach echoes the postwar reconstruction of Aleppo between 2016 and 2020, which was also led by the same regime responsible for much of the destruction and violence.[6] In Aleppo, reconstruction plans under the previous government of President Bashar al-Asad reinforced the state’s economic and spatial dominance over the city by prioritizing regime-backed real estate investments and the interests of its allies rather than the recovery of the city and its people.

On July 12, 2025, the head of the Sudanese army, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, announced the creation of the Higher Committee for Preparing the Environment for Citizens’ Return to Khartoum, claiming its mission to be restoring normal life and removing what the authorities describe as negative practices. In practice, new security measures have been imposed that displace many of Khartoum’s informal housing dwellers who are accused of supporting the RSF and targeted on racialized grounds—particularly those who are thought to originate from western Sudan, where the RSF draws much of its support. At the same time, reconstruction efforts appear to be expanding SAF-owned institutions and industries under the guise of reviving the city’s economy and services, including the rehabilitation of a meat processing complex by the Defense Industries System.

The army’s approach to reconstruction seems to reproduce the same colonial and postcolonial logics of securitization that have long shaped Khartoum’s geography and politics, and inspired citizen uprisings. While the plan signals a responsible intention for the city’s reconstruction and recovery, its framing and implementation risks perpetuating inequalities and stoking future conflicts.

For the people of Burri, the siege and armed fighting may have ended, but restoring life to what it once was feels far from reality, as the scars of what they witnessed run deep. Healing will require more than reconstructing roads and buildings through business as usual; it demands investing in trust between authorities and the community, recognizing shared loss and supporting collective recovery.

[Niema Alhessen is an independent researcher focusing on urban conflict and displacement.]

Support MERIP in providing critical, grounded reporting and analysis without paywalls. Make a one-time or monthly donation today!

[1] The interviews for this article were conducted in Egypt and remotely with people in Sudan in July 2025. All names have been changed to protect their safety and privacy.

[2] Marina D’Errico, "The Urban Fabric between Tradition and Modernity (1885–1956): Omdurman, Khartoum, and the British Master Plan of 1910," Africa in Global History (July 2023).

[3] Robin Cormack, “Planning the Colonial Capital: Khartoum and New Delhi,” in Sofia Greaves and Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, eds. Rome and the Colonial City: Rethinking the Grid (Oxford and Philadelphia: Oxbow Books, 2022).

[4] Omar Ferwati, “Fault Traces: Civilian Architectural Responses in the Syrian Civil War,“ Master’s Thesis (University of Waterloo, 2020).

[5] Armina Pilav, “Before the War, War, After the War: Urban Imageries for Urban Resilience,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 3/1 (2012).

[6] Myriam Ferrier, “Rebuilding the City of Aleppo: Do the Syrian Authorities Have a Plan?” (Robert Schuman Centre/European University Institute, 2020).