Fiber Optics and the Hidden Politics of Connectivity

On February 18, 2024, Houthi forces in Yemen fired two ballistic missiles at the MV Rubymar, a Belize flagged, British owned, bulk carrier cargo ship.

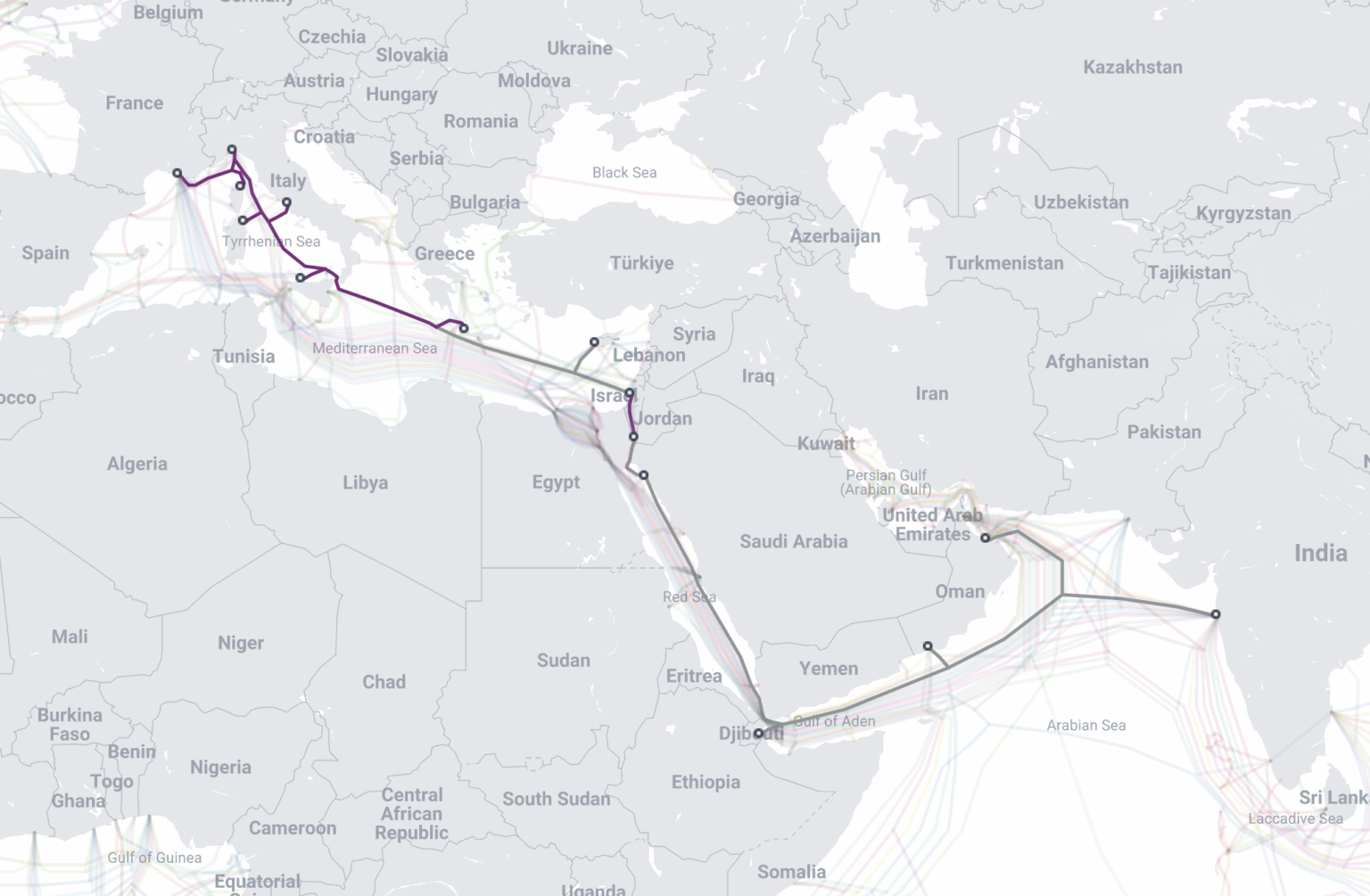

The crew dropped anchor and evacuated, but the ship began to drift. Six days later it crossed the path of three intercontinental submarine data cables—the Europe India Gateway, TGN-Eurasia and Asia-Africa-Europe 1. Moments later, they went dark. Analysis of the internet outages and satellite imagery of the Rubymar’s journey strongly suggest the ship’s trailing anchor severed the cables, disrupting 25 to 70 percent of internet traffic between Europe and Asia.

Despite being buried deep in trenches on the seabed, these fiber optic cables became unintended casualties of Israel’s regional war and the struggle for Palestinian liberation. The Houthi movement’s series of attacks on Red Sea commercial shipping traffic began in November 2023 as a direct response to Israel’s bombardment of Gaza.

The rupture of internet traffic briefly exposed what is usually hidden: As a material network circulating information and capital, telecommunications cables are deeply embedded in the political geography of the regions they traverse. Their routes are determined as much by international relations and economic incentives as they are by technical calculations about geospatial features and transmission speeds. In the Middle East they are a site of conflict and collaboration, vulnerable to regional tensions and potential conduits of normalization between Arab states and Israel.

When infrastructure works as intended, it can be hard to detect and indistinguishable from the ambient environment of everyday life. Often it is not until something goes wrong that the systems undergirding our world become visible. Accidental cable cuts are common with roughly 150–200 faults a year, most of which are caused by trailing anchors. These mundane breaks are usually repaired within weeks or even days and rarely reported on outside of the industry press. The Rubymar outage was different. Security concerns in the Red Sea made it too dangerous for a repair vessel to approach the damaged cables, and what might have passed as another routine fault instead raised new anxieties about the vulnerability of global networks amid an escalating war.

Those anxieties quickly spilled into politics. Following the incident, calls for alternative routes to circumvent potential threats in the Red Sea grew louder. Some alternatives, like Cinturion’s Trans Europe Asia System (TEAS) and Google’s Blue-Raman cable system propose terrestrial routes across the Arabian Peninsula, potentially creating a direct infrastructural bridge between Israel, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states—projects that would both enable and be enabled by the normalization of relations with Israel. Indeed, the existing plans to secure the network appear to depend on Saudi Arabia establishing economic relations with Israel.

Normalization between Arab states and Israel is broadly understood as a public-facing political rapprochement, intertwined with negotiations for Palestinian statehood, that involves opening borders, exchanging diplomats and activating economic corridors. But it also operates informally through material economic processes, driven by colonial logics and elite incentives at the expense of the rights and freedom of Palestinians. Like infrastructure itself, when informal normalization works as intended, it is often obscure, operating beneath the surface and preceding public pronouncements of collaboration or reconciliation. Through the example of fiber optic cables, it is possible to see how normalization might advance materially even in contexts such as Saudi Arabia, whose leaders continue to insist that formal recognition of Israel depends on Palestinian statehood.

While it often feels as though the internet is everywhere, its backbone infrastructure can be broken down into material units pinned to a map. The world is strung together by a tangle of cables that determines the routes that internet traffic takes between countries and continents. Fiber optic cables transmit information as light signals, pulsing through glass tendrils across the planet’s surface in a matter of milliseconds. They are the nervous system of global governance, capitalism and war.

Most cables run underwater. To get from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean, however, requires taking one of various overland routes through Egypt and then underwater into the busy maritime thoroughfare of the Red Sea. There, 22 cables converge, each no thicker than a garden hose, carrying as much as 90 percent of internet traffic between Europe and Asia. As the most densely cabled place on the planet, estimates claim that roughly 17 percent of the world’s internet runs through this bottleneck.

Egypt’s monopoly over Red Sea crossings has long been sustained not only by geography but by the refusal of Arab states to use Israel as an alternative pathway.

The physical limitations on this route are costly for operators and constitute a vulnerable point of failure in the global network. While accidental cable cuts are common, the lack of redundancy in the Red Sea means that an incident like the sinking of the Rubymar can have an outsized impact on global communications and economic networks. The route has also created an institutional bottleneck in Egypt. Its National Telecom Regulatory Authority has allowed Telecom Egypt—originally a public utility that continues to be 70 percent state-owned—to retain a de facto monopoly, enabling it to charge ever higher tariffs for installation and transit. As a result, routing a cable across the Egyptian isthmus nearly doubles the cost of a connection from Europe to East Asia.

Egypt’s monopoly over Red Sea crossings has long been sustained not only by geography but by the refusal of Arab states to use Israel as an alternative pathway. When Gulf states now explore terrestrial routes that would connect directly to Israel, such as TEAS or Blue-Raman, they are quietly reconfiguring the political and communications geography of the region.

In 2023, British telecommunications consultant Julian Rawle wrote that, “the only thing sustaining Egypt’s stranglehold on the Europe-Asia route for submarine cables was Arab distaste for dealing with Israel as the logical alternative.”[1] But things are changing. Saudi Arabia’s aims to diversify away from a hydrocarbon dependent economy and its competition with the United Arab Emirates to develop a digital hub—in addition to Egypt’s monopoly and the dangers of the Red Sea route—provide the economic motivation to pursue the alternative path across the Arabian Peninsula, through Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Israel.

Normalization is often depicted as a diplomatic threshold on the horizon, something that can be leveraged in negotiations around regional security. Several Arab states have officially passed this threshold with Israel: Egypt in 1979, Jordan in 1994 and more recently the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan under the 2020 Abraham Accords. Even where these formal treaties exist, however, the deeper work of normalization takes place through infrastructure, finance and technology—domains that embed Israel into a regional economy regardless of public opposition.

The UAE presents the most advanced case: Despite public discontent, its government has deepened normalization even during the destruction of Gaza. It has leveraged the Abraham Accords as diplomatic capital in Washington and as an engine to fuel trade and develop the technology sector. Saudi Arabia’s trajectory is more ambivalent. While Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has publicly condemned Israel’s war on Gaza as genocide and reaffirmed that recognition of a Palestinian state remains a precondition for normalization, reports suggest Riyadh is open to incremental steps if they can be framed as progress toward Palestinian statehood.

Moreover, much of the momentum toward normalization has come from private sector ventures in technology and infrastructure. Israeli start-ups, Gulf sovereign wealth funds and US-based multinationals have already partnered through trilateral investment structures, often using US firms as intermediaries to channel Israeli innovation into Saudi or Emirati projects. Companies like Google and Amazon plan massive regional infrastructure projects that depend on Saudi, Emirati, Jordanian and Israeli cooperation.

The TEAS and Blue-Raman systems are examples of this private sector collaboration. Both projects are considered critical components in the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), a proposed trade and infrastructure initiative announced at the 2023 G20 summit, which will link India to Europe via shipping and railway routes through the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Israel. The IMEC satisfies dual US foreign policy objectives: to continue building momentum toward normalization following the Abraham Accords and to develop an economic and strategic bloc in the Middle East to deter Iran and China.

TEAS was announced in 2020 as a proposed 20,000 km network linking Mumbai to Marseille via the Middle East. The project is under development by a new provider, Cinturion Group, which signed a mandate letter with the International Finance Corporation, the private sector arm of the World Bank, for a proposed loan to finance the project in 2023. Cinturion has confirmed landing partners for the system in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, UAE and Oman as well as partners in Europe and South Asia. Although the company has not announced a Memorandum of Understanding with an Israeli landing partner, official documentation about its network lists cable landing stations in the Israeli Mediterranean coastal cities of Rishon and Ashkelon. The project is also partially owned by the Israeli investment firm Keystone and is supported by Saudi’s GCC Interconnection Authority. As with many of the IMEC-related projects, there has been little news about TEAS during Israel’s war on Gaza. In September 2024, however, the company presented the advantages of the terrestrial route at an industry conference, indicating that the project is still in development.

The Blue-Raman system is being developed by the Subsea division of Google, representing a relatively new industry dynamic where so-called hyperscaling technology companies, like META and Google, fund, construct and operate their own infrastructure. This system breaks from an older model in which financing and design were shared among members of telecoms consortia. Google Subsea’s planned $400 million network will run between India and Italy avoiding Egypt by travelling overland through Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Oman. The system is split into two segments: Blue, connecting Europe to Israel, and Raman, extending from Jordan to India. Together they span roughly 11,700 km with a design capacity of more than 200 terabits per second. Originally expected to be ready for service in 2024, current projections indicate the cable will be operational by the end of 2025.

These projects show how normalization is pursued materially through infrastructure even when it is politically contested and before any official agreements are signed.

These projects show how normalization is pursued materially through infrastructure even when it is politically contested and before any official agreements are signed. While these plans to lay fiber optic cables across the region emerge from the private sector, the companies depend on the licensing authority in each country to grant them permission to land and operate. The projects are complex bureaucratic objects that require state oversight to traverse exclusive economic zones, territorial waters and national borders. Cable systems often emerge from public-private multilateral collaboration. In these cases, normalization begins with technical and economic decisions taken by elites in the private sector, which then make political coordination more likely or even unavoidable.

Both TEAS and Blue-Raman have been pursued quietly and without fanfare in the Gulf, especially when compared, for example, to the domestic Saudi Vision cable, connecting Jeddah, Yanbu, Dibba and Haql. The latter was celebrated as a symbol of the kingdom’s bright techno-future and strategy to supplant Egypt as the regional hub of cable infrastructure. While much larger and more ambitious, the terrestrial systems connecting Israel to the Gulf will be difficult to celebrate as symbols of national progress without inviting criticism from a population that still largely opposes cooperation with Israel.

Cultural theorist Raymond Williams points out that etymologically “to communicate is to make common.”[2] Telecommunications infrastructures are machines for manufacturing new commons. The technology of communication cables naturally complements the myths and metaphors of normalization, promising unity and prosperity by intertwining regimes in shared circuits of trade, infrastructure and surveillance.

The fiber optic systems are sold with glossy marketing copy that promise to “strengthen the connection between India, the Middle East and Europe” (Cinturion) or to provide “connectivity to power their online lives, and communicate with friends, family and business partners” (Google’s vice president and head of Global Networking).[3] In this discourse, integration is imagined as an inevitable good, connecting populations and dissolving enmity. This rhetoric, however, masks the colonial and capitalist logics of surveillance and control that drive many communication infrastructure projects in the region.

For Google and Cinturion, the incentive to pursue these projects lies in capturing a new segment of the market and providing a more secure route for information traffic from Europe to Asia. For the countries where they would operate, the incentive lies in the promise that this infrastructure will help develop their digital economies.

While Israel is one of the best-connected places on the planet in terms of intercontinental fiber optic capacity, the state has limited the development of mobile and broadband connectivity in Gaza…

While Israel is one of the best-connected places on the planet in terms of intercontinental fiber optic capacity, the state has limited the development of mobile and broadband connectivity in Gaza and used its control of the material infrastructure to enforce internet and telephone blackouts as part of a military strategy. Moreover, Google was recently named in UN Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese’s report on the economy of genocide for its development of public cloud infrastructure that supports AI systems Lavender, Gospel and Where’s Daddy?, used by the Israeli army to generate lists of civilian targets for murder in Gaza.

The vulnerabilities of the Red Sea bottleneck, Egypt’s monopoly and the search for alternative terrestrial routes all demonstrate how the architecture of the fiber optic cable network is politically contingent and its security depends on regional relationships. Projects like TEAS and Blue-Raman show how normalization can advance quietly—even amid public opposition and as Israel’s control of cables and cloud systems enables strategic internet blackouts and surveillance programs in Gaza. By determining who can transmit, receive and control information across the region, these networks simultaneously empower Gulf and Israeli economic ambitions and constrain Palestinian access, making infrastructure a key instrument in shaping regional power and undermining Arab solidarity and the pursuit of Palestinian sovereignty.

[Ned Leadbeater is a recent graduate of the University of Oxford, where he completed an MPhil in Modern Middle Eastern Studies with research on the material politics of the internet in Egypt.]

[1] Julian Rawle, “Out of the Frying Pan and Into the Fire?,” Submarine Telecoms Forum 128 (January 2023), p. 49.

[2] Raymond Williams, “Communication,” Keywords: A vocabulary of Culture and Society (London: Fontana Press, 1988), p. 72

[3] “Teas—An Open-Access System,” Cinturion Group website; Bikash Koley, “Announcing the Blue and Raman subsea cable systems,” Google Cloud Blog, July 29, 2021.

Ned Leadbeater, "Fiber Optics and the Hidden Politics of Connectivity," Middle East Report 315/316 (Summer/Fall 2025).