Paradise Now's Understated Power

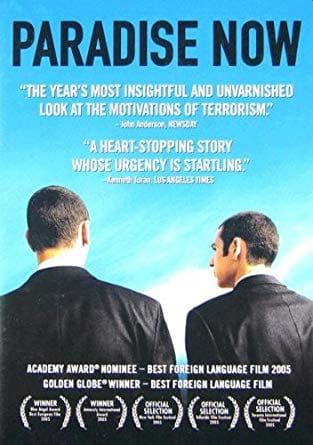

Joining Ang Lee, director of the gay cowboy epic Brokeback Mountain, among the winners at the January 16 Golden Globes award ceremony was the director Hany Abu-Assad, a Palestinian born in Israel whose Paradise Now took home the prize for best foreign language film. While critics of all persuasions